By Emma Malinak

Solar energy seems like the least controversial renewable energy source, but government hearings for proposed solar projects in Rockbridge County haven’t been sunny.

The meetings, typically quiet with dozens of empty chairs, have been packed lately with passionate residents who oppose the projects planned for Natural Bridge Station and Raphine. One local even cried as she claimed the projects would “poison” the county’s land and people.

Others fear that solar projects will erode farmland and destroy scenic views.

But some, like James G. Alexander Jr., who is renting 30 acres of his Fairfield farm to a solar company, say that Rockbridge County is a good home for renewable energy.

“If we’re serious about doing clean energy, we’re going to have to put something somewhere,” Alexander said. “We can’t use this ‘not in my backyard’ mentality with everything.”

“If we’re serious about doing clean energy, we’re going to have to put something somewhere,” Alexander said. “We can’t use this ‘not in my backyard’ mentality with everything.”

For Alexander, the solar project is his best path to a stable retirement. He said the money he gets from the solar company is “a better deal” than selling or renting the plot to another farmer. Plus, diversifying his sources of income makes him feel more secure.

Indeed, it’s harder than ever to run a family farm, with climate change prompting more severe and irregular weather, globalization causing crop prices to drop and corporate farming companies forcing smaller farms out of business. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 200,000 farms closed across the country from 2007 to 2022, and farm sector income is expected to drop by more than $30 billion from 2022 to 2023.

Farmers’ property rights called into question

Alexander said he used to grow alfalfa and corn on the 30-acre plot between Interstate 81 and U.S. Route 11 that is now under construction to become a five-megawatt solar array, the name for a group of panels. He said he doesn’t miss the land — he still has more than 400 acres to use for daily farm operations.

But some locals worry that, with increased development of all kinds, there isn’t enough good farmland to go around now, let alone enough to convert for future solar projects.

“This is not solely an issue of property owners’ rights,” Steve Hart, a Lexington resident, said at Board of Supervisors meeting on Nov. 14. “It’s not the same because farmland is a precious, natural and national resource. Its destruction impacts us all.”

Many locals sided with Hart when the proposed Natural Bridge Station project was reviewed in a Board of Supervisors public hearing on Nov. 27. The 21-acre plot being considered sits on Douglas Braford’s farm at the intersection of Lloyd Tolley Road and Gilmores Mill Road.

Braford’s neighbor, Theresa Bullock, said the three-megawatt array would be closer to her front door than his. She diversified her income by opening an Airbnb on her farm, and she worries that the solar project would significantly decrease business by turning away guests who visit for the scenic views.

“I’ve been really conflicted about this whole situation,” Bullock said at the public hearing. “[Braford] has been through hard times lately, and I want to support him in what he’s chosen to do with his land. But I also have to protect my family and what we are doing with our land.”

Solar trends in the county and the nation

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, renewable energy sources such as solar power are key to supporting “the nationwide effort to meet the threat of climate change.” Transitioning away from fossil fuels and adopting renewable energy reduces the greenhouse gas emissions that exacerbate changing weather patterns.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality set a goal in 2019 to have all of the state’s electricity produced from carbon-free sources, such as wind, solar and nuclear energy, by 2050. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, 6.16% of Virginia’s electricity comes from solar power today, with just under 4,500 megawatts of arrays installed statewide.

Assistant Professor of Economics at Washington and Lee University Alice Tianbo Zhang said solar power has economic benefits, too. It is cheaper than fossil fuels in terms of cost per unit of energy generated, and it opens opportunities for economic growth.

“If our objective is to bring in business development opportunities, bring in jobs, bring in a lower cost of energy, bring in higher government revenue — solar is a no-brainer,” Zhang said.

Large tracts of flat land with lots of sun exposure are ideal for solar arrays, she said, which puts farmland in high demand for solar companies.

Chris Slaydon, director of Rockbridge County’s office of community development, said about 70% of the county is zoned for agriculture, so new project applications are always crossing his desk.

Since 2019, the Board of Supervisors has granted special exception permits to two solar companies. One company is building arrays on Alexander’s farm now, and the other finished construction on a 14.5-acre plot on Walkers Creek Road in Rockbridge Baths in 2021.

Now, US Solar’s proposed Natural Bridge Station project and Volcano Energy’s proposed 65-acre solar array in Raphine are on the table. The Planning Commission voted 3-1 to recommend denial of special exception permits for both projects on Oct. 11, after about 30 local residents expressed their opposition.

The Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to continue the Natural Bride Station project’s public hearing until Jan. 8, citing the need for more time to address the community’s concerns. The public hearing for the Raphine project has not been scheduled yet.

Misunderstandings lead to community-wide anxiety

Slaydon said the two proposed projects are at a disadvantage because they are visible to neighbors.

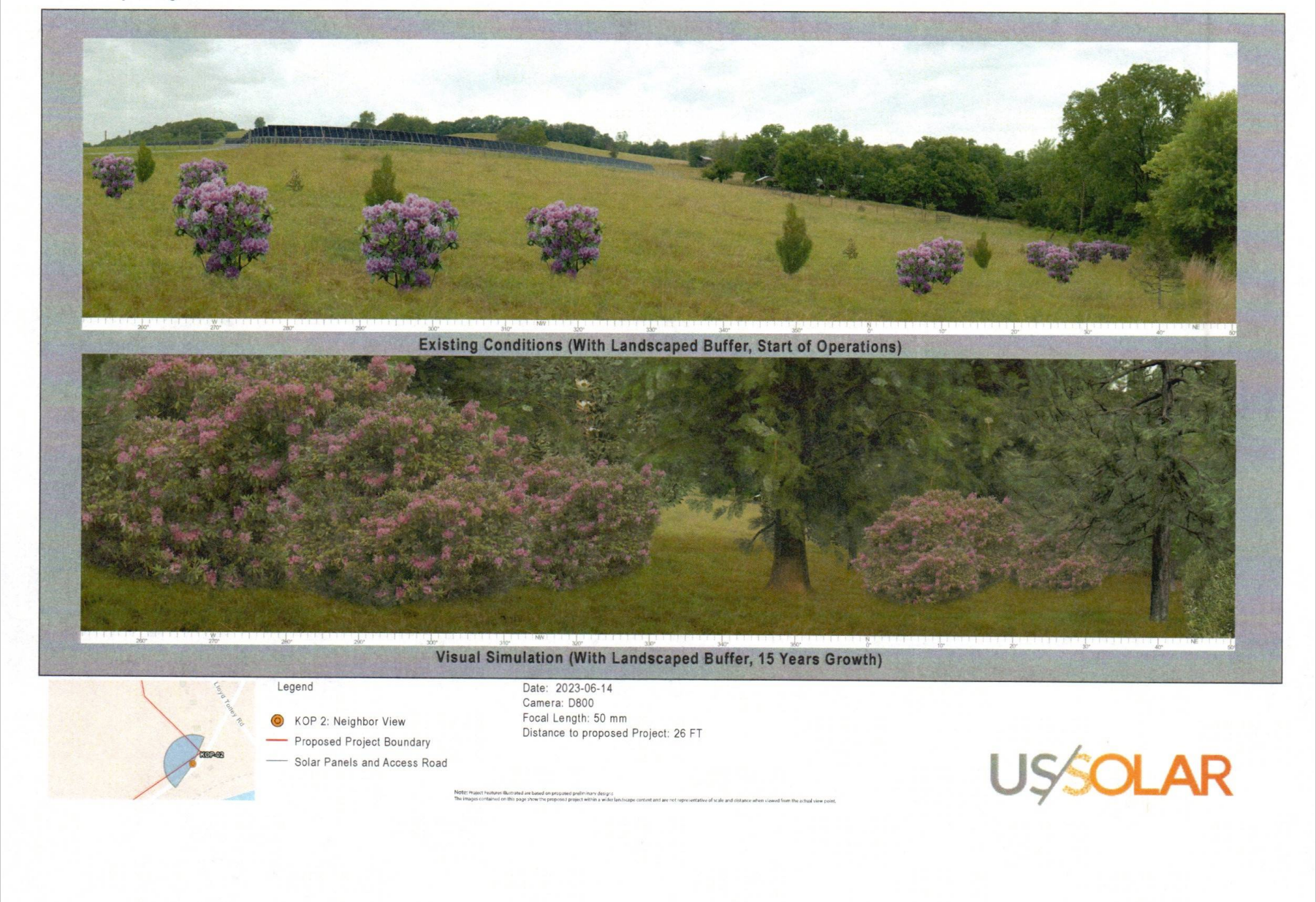

About half of the residents who spoke during the public hearing for the Natural Bridge Station project mentioned their concerns about the destruction of their “viewshed,” meaning their panoramic outlook from their property. Their descriptions of the arrays ranged from “very ugly” to “absolutely egregious,” with emphasis placed on the height, glare and noise of solar panels.

Dan Csaplar, the project manager of the proposal, said at the hearing that panels are no more than 8 feet tall and won’t be disruptive to the neighborhood.

“The arrays emit less of a glare than blades of grass,” he said. “From the transformers, the typical sound level is roughly that of a hum of a library.”

Rockbridge County Farm Bureau President Mack Smith said his main concern isn’t the loss of the view, but the loss of the land.

“We’re not opposed to solar panels, unless they’re on good farmland,” he said at the hearing. “Preservation of farmland is critical to our future and our national security.”

Csaplar said the land being considered for the site is not prime farmland due to its soil type, citing a study conducted by Tom Stanley, county agricultural extension agent.

Other concerns about the array ranged from runoff to radiation.

Csaplar said native vegetation will be planted around and under the completed panels, and those root systems will help control runoff. He also assured that the panels have passed tests that prove they are not toxic to the environment.

According to the Alliant Energy Corporation, solar panels only generate low levels of non-ionizing radiation — the same kind of energy that is transmitted by radio and TV waves, cell phones and microwaves.

Those opposed to the projects say US Solar will be taking resources away from Rockbridge County without giving anything back in return.

In fact, US Solar owns about 80 solar arrays concentrated in the region surrounding its Minnesota headquarters. The company runs what it calls a “sunscription” service which “allows electric customers in one place to benefit from a solar project located somewhere else,” according to its website. There are more than 5,000 active users who pay US Solar for the energy that panels generate and, in return, get a reimbursement for their electric bill.

While Rockbridge residents won’t be seeing a share of these reduced electricity prices, Slaydon said US Solar will still be paying up. The company will owe the county five years of rollback taxes for bringing part of Braford’s property out of agricultural use, and it will pay $15,000 per acre and $1,400 per megawatt in taxes as well, Slaydon said.

An ordinance in the works

Slaydon said residents’ worries are valid, but not necessarily unique to solar projects.

“It is mainly a viewshed concern and a loss of farmland concern,” he said. “The same could be said about housing development. I think a lot of the fear is just that solar is so new.”

Rural counties across Virginia have responded to that fear by approving ordinances that place caps on how much of a county’s land can be allotted for solar arrays. Since March, Henry, Mecklenburg and Pittsylvania counties have adopted such ordinances, according to Cardinal News.

Slaydon said Rockbridge County officials have been considering a solar ordinance for about two years but hadn’t pushed for its adoption until the recent tensions emerged. He said he isn’t sure if the ordinance will include an acreage cap like other counties, but he knows it will “streamline the process” of reviewing solar companies’ project applications.

The ordinance should be on the books by the first quarter of 2024, Slaydon said. In the meantime, the Board of Supervisors must determine the future of the Natural Bridge Station and Raphine projects without guidance from local laws.

Zhang said the decisions county officials make now will set the tone for how solar companies —which she describes as “potential investors” — interact with Rockbridge in the future.

“Renewables are the future,” she said, “and if Rockbridge County doesn’t take this opportunity, there are plenty of other counties nearby that would, happily.”